In April 2024, NASA scientist Chad Greene flew with a team of engineers aboard a Gulfstream III and monitored a radar instrument as it explored the Greenland ice sheet below. Flying about 150 miles east of Pituffik Space Base in northern Greenland, Greene took this photo from the plane window showing the vast, barren expanse of ice sheet. Then the radar unexpectedly discovered something buried in the ice.

“We were looking for the ice bed and Camp Century popping out,” said Alex Gardner, a cryospheric scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) who led the project. “We didn’t know what it was at first.”

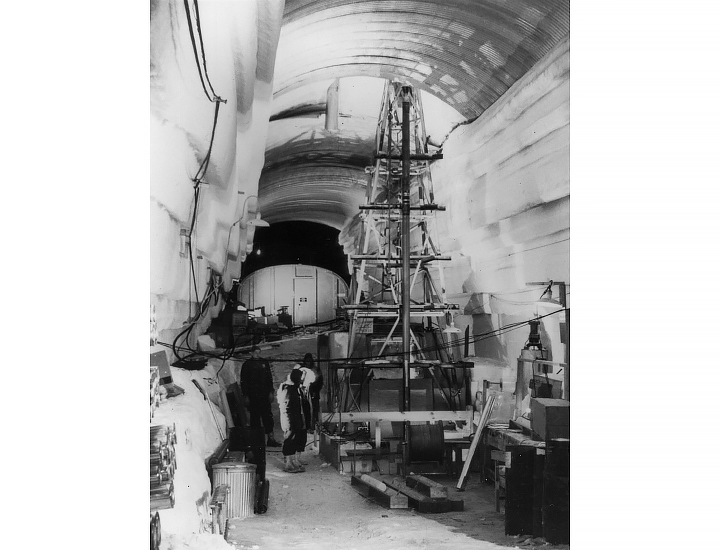

Camp Century, also known as the “City Under the Ice,” is a relic of the Cold War. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built the military base in 1959 by cutting a network of tunnels into the near-surface layer of the ice sheet. After its abandonment in 1967, snow and ice continued to accumulate, and the solid structures associated with the facility now lie at least 30 meters (100 feet) below the surface.

Radar measures distances by emitting radio waves and measuring how long it takes for them to be reflected back to the sensor. Like ultrasound for ice sheets, scientists can use radar to map the ice surface, its inner layers, and the underlying bedrock.

Previous aerial surveys that flew over Camp Century have discovered traces of the base in the ice. These flights used conventional ground-penetrating radar that points directly downward, producing a 2D profile of the ice sheet. In this view (map below), Camp Century’s solid structures appear like a speck in the deformed ice sheets.

However, during the April 2024 flights, NASA’s UAVSAR (Uninhabited Aerial Vehicle Synthetic Aperture Radar) was mounted on the belly of the aircraft. The system looks down and to the side, producing maps with more dimensionality.

“In the new data, individual structures in the Secret City are visible in ways that have never been seen before,” said Greene, also a cryosphere scientist at JPL. Comparing the new radar map of Camp Century (shown at the top of this page) with historical maps of the base’s planned footprint, the parallel structures appear to be consistent with the tunnels built to house a number of facilities.

The added dimension also means that interpreting the images can be challenging. For example, the long line that appears “above” the base is the ice floor, which lies at least a mile below the surface of the ice sheet and well below the depth of Camp Century. In this view, the ice bed appears above the base because the radar echo shows part of the ice bed far in the distance.

Scientists have used maps captured by conventional radar to support estimates of Camp Century’s depth – part of an attempt to estimate when melting and thinning of the ice sheet would clear the camp and any remaining biological, chemical and radioactive waste buried within it could expose with it. The scientific utility of Camp Century’s new UAVSAR image remains to be seen; for now it remains a novel curiosity acquired by chance.

Greene and Gardner did not set out to capture the image of Camp Century. “Our goal was to calibrate, validate and understand the capabilities and limitations of UAVSAR for mapping the inner layers of the ice sheet and the ice-soil interface,” Greene said. Ultimately, such instruments are intended to help scientists measure the thickness of ice sheets in similar environments in Antarctica and constrain estimates of future sea level rise.

“Without detailed knowledge of ice thickness, it is impossible to know how ice sheets will respond to rapid warming of the oceans and atmosphere, severely limiting our ability to predict the rate of sea level rise,” Gardner said. The test flights that captured Camp Century earlier this year will enable the next generation of mapping campaigns in Greenland, Antarctica and beyond.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Michala Garrison and Jesse Allen using UAVSAR data and images by Chad Greene (NASA/JPL-Caltech) and IceBridge UHF ice penetrating radar data by Joseph MacGregor (NASA/GSFC). Historical photo courtesy of the National Archives, Photo ID 404791598. Story by Kathryn Hansen.